Munich is one of my favorite German cities, and every time I go back I'm reminded why - it's the only large city I've been to that feels small and friendly, and everywhere you look there's something new and different. The omnipresent beer gardens don't hurt either. We were in Munich over the weekend visiting family (making it my third visit this year), and we took the time to explore some of the areas that we hadn't been to before. Dachau was one of these places - it was one of the largest concentration camps on German soil and it's been kept in almost the same condition that it was in when the Americans liberated it. The museum in the complex is very moving and extremely detailed - we stayed for four hours and only left because it was closing - and covers almost every aspect of life in the camps and the repressive excesses of the Nazi regime. One of the most interesting and terrifying buildings is the "bunker", a sort of prison within a prison at the camp. Prisoners were kept in solitary confinement and darkness for up to two months, and oftentimes the only sound that they would hear was a gunshot at 2 AM - signifying the execution of a fellow prisoner. In an appropriately ironic twist, the German guards who ran the camp were held prisoner here by the American forces before their execution. The experience was one of the most moving that I've had in Germany.

Despite the horrors of Dachau, we managed to enjoy one of Munich's greatest assets - the English Garden. It's essentially an enormous park in the middle of the city (larger than Central Park) which contains two artificial rivers, a lake complex, a faux-Greek temple, and, my personal favorite, a wooden Chinese pagoda. The pagoda is surrounded by an equally impressive beer garden (over 7,000 seats!) run by the Hofbrauhaus, the former Royal Brewery of Bavaria. Like most beer gardens, you can buy beer by the liter. I can report, after much scientific study, that it is delicious.

We only stayed in Munich for two days, and on the second day we decided to visit a museum. We had noticed that there was an exhibition about King Tut's tomb - and in our excitement we forgot to check the reviews of the exhibit. This mistake turned out to be fatal, as there were no original artifacts (for some reason Cairo didn't want to share), so all of the "artifacts" on display were (rather cheap) copies. Instead of precious stones, gold, and superior craftsmanship from a vanished culture, we saw painted wood. After this dissapointment we were out of time, so we were unable to visit the BMW museum or the Alte Pinakotek (the two main sights I wanted to see on this trip, ironically) - but there's always next time.

As always, the interested can view photos here.

Sixty days ago, a novel flu strain from Mexican pigs brought the world to a minor panic. As the data started to come in, it looked as if the strain was a serious illness in young, healthy victims - the same pattern seen with the 1918 outbreak. The initial mortality rate was just under 10%, a shockingly high figure, but after the first two weeks the rate had dropped down to 1%, mostly a result of more thorough testing of those with flu-like symptoms. In that same time frame, pig farmers and the pork lobby fought to change the name from "swine flu" to "Influenza A (H1N1)", a change which the WHO adopted. While it may seem a bit silly, the name change helped to reduce panic - think about how many warnings you got to avoid eating pork (which is just silly - cooking the pork would kill the virus, and even if you ate truckloads of infected raw pork, which I don't recommend, the viral particles are not going to survive the passage through the intestinal track. Within three weeks, global coverage of H1N1 dropped to a trickle. If the virus is mentioned today, it is usually in connection with the first death in a new country.

Ironically, the situation has worsened since the 24-hour coverage stopped. On June 11, 2009, the WHO declared a pandemic (a global epidemic). While this sounds scary, it just means that spreading in more than one global region (and the way that they define global regions is quite screwy) which cannot be traced back to a direct chain of person-to-person transmission. This criterion is easy to meet, and if you go back and look through the data (which the WHO has here), you can see that the conditions for a Level 6 pandemic were met at least one week before the declaration, and the WHO has admitted to waiting to make the announcement for political reasons (i.e. until the panic died down). Indeed, speculation as to when the announcement would be made was bouncing around the media for quite some time beforehand (do a search for "swine flu level 6" and look at the dates on the articles).

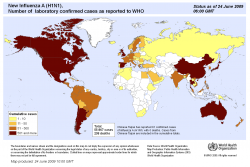

So what happens now? Is H1N1 still a threat? The answer to both questions is that we simply don't know. Flu season is over in the Northern and Southern hemispheres (where most of the developed world is located), but flu season never ends in the tropical belt - which is inhabited by a much larger percentage of the world's population. Unfortunately, this region of the world is also the one in which medical surveillance (and general medical care) is much weaker than the rest of the world - so for almost all practical purposes the virus is going to go silent for a few months before reemerging - and it will reemerge - when flu seasons begins again. For a graphic showing how severe this surveillance problem is, check out the map below (source) - it's hard to believe that the belt stretching from Southeast Asia to South Africa has so few cases (pay special attention to the scale of the colors, they are somewhat misleading - 501 cases is the same as 5,001 cases). When the virus reemerges, it could have combined with H5N1 or other flu strains, or it could have been weakened - we simply don't know and there's no real way to predict it. I agree with the WHO's generally philosophy on the issue, which is to hope for the best but prepare for the worst.

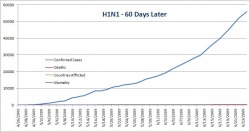

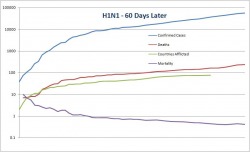

Now that we've got the background and the dangers covered, how severe has H1N1 actually been? The WHO has been kind enough to publish all of their data, including confirmed cases and mortality broken down by country ( here). I used these data to make up a graph showing confirmed cases, mortality, number of countries afflicted, and mortality rate over time. As you can see below, when you use a standard y-axis the mortality is so low that you can't even see it when compared to the overall number of cases (for the record, the mortality rate is about 0.4% - slightly higher than, but on the same order of magnitude as seasonal flu) Since using a normal axis wasn't very helpful (it's hard to extract data from a graph that you can't read) I also made a log scale graph. It looks slightly scary, but please, pay attention to the numbers on the y-axis and note that the values increase logarithmically. On this graph it's fairly easy to see that while both the confirmed cases and mortality are still climbing, the overall mortality rate is fairly constant. I attempted some curve-fitting to these lines (power regressions) but the r-value was too low for the trendlines to mean anything - so we need to wait on more data before we can make any real predictions. In this case the x-axis has the same scale as the above graph. If anyone wants the original Excel file, let me know and I'll send it to you. To conclude, I'd like to give a short caveat about this data set. It's likely that it underestimates the total number of confirmed cases (how many people with flu-like symptoms have not been tested for H1N1 around the world?), while the total number of deaths is likely to be fairly accurate - if someone dies from flu-like respiratory symptoms their blood will probably be tested. Given these two assumptions (and I stress that they are assumptions), the mortality rate may be slightly lower than the data suggest, which is certainly a Good Thing. Although we now have much more data about this pandemic virus, which appears to be much less deadly than originally feared, there's still a lot of factors that are outside of our control. What happens if the virus mutates or recombines? What effect will it have on the immuno-suppressed (AIDS victims and people with chronic parasite infections, both of which are most common in the developing world)? These are all good questions, and although we can use the data (yay epidemiology!) to help make predictions, until flu season starts again we can't say anything for certain.

Bacteria are everywhere. It's estimated that there are over 100 trillion (with a t) individual bacteria living in the average humans digestive tract. While it sounds fairly disgusting (unless, of course, you're a microbiologist), their presence is actually a Good Thing - these bacteria help us to break down and digest foods that we would normally not be able to eat on our own. However, sometimes this symbiosis has some unintended consequences, as this wonderful paper in PLoS ONE shows.

Normally, our immune systems are used to the presence of our gut microbiota, but sometimes (fairly rarely) they provoke a spontaneous immune response. Since it's not the body itself which causes the heightened immune response, it's not an autoimmune disorder, but the symptoms are very similar - in both cases, the body's immune system ends up attacking itself, which in the intestinal tract leads to Crohn's Disease and/or inflammatory bowel disease. These conditions then increase the risk of colon cancer. What this paper demonstrates is that modulation of the gut microbiota is enough to provoke this heightened immune response - and possibly lead to colon cancer. Should you have time, it's a good read (it does get a bit technical though) but the real highlight (for me at least) is that it underscores the major role that bacteria play in just about everything.

While checking my email this morning, I noticed an urgent (not even kidding) message from AStA (a national student-government type thing. It's very odd) informing me that the occupation of one of the lecture buildings will continue. They invited all of us to take part in the events that they are hosting, like documentaries and discussion sessions (this is a Serious Protest). The occupiers have run into a bit of a snag - the building that they chose to occupy houses the library for political science, and the undergraduate thesis for political science students was supposed to be due on Monday. As a compromise, they've managed to extend the deadline for the thesis by three days - but as the occupation is continuing, this extension will not be a big help. Rest assured, they are "trying" [sic] to make the library available. Good to keep the priorities in order here - finshing your bachelor's thesis=bad, discussing documentaries and alternative workshops=good. Score one for the Bildungsstreik!

Continuing the hilarity, they've issued another list of demands, this one more riduculous than the last. High points include: "Removal of compulsory attendence from the entire social sciences" and the too-awesome-to-be-true "two-hour lunch break and class-free Wednesday afternoons to encourage collaboration and active participation in student committees." Again, please don't misunderstand me - I think that it's good that students are trying to take control of their education, but they're going about it in entirely the wrong way (potentially screwing your fellow students out of a degree is not the way to make friends) - and there's still not a compromise in sight.

For those of you who can read German, I've linked the original email here.

Johannisnacht is a relatively new festival - it's only been held since 1967 - but it reaches back to Mainz's history, especially that of its most famous son, Johannes Gutenberg. After the invention of the printing press, an entire industry sprang up around printing, complete with a printer's guild and the necessary apprentices. Upon completion of their training, the apprentices would be dunked in water in a ceremony known as "Gautschen", which was supposed to "ritualistic cleanse of the impurities they had commited during their time as apprentices" (it would seem that some things never change) - but was really just taken from the old custom of depostion. Once the apprentices had been dunked, they received a certificate confiming that they had gone through the process to ensure that they wouldn't have to repeat it. When the traditional methods of printing books started to fall by the wayside, the "Gautschen" went with it - until Johannisfest was started. The Gautschen serves as one of the festival's high points, and the organizers take great pains to make it seem "authentic" - from the man dressed in period costume reading the names off the list to the certificates given out to the dunkees at the end of the day. Interestingly, the term "apprentices" has adapted to the changing times and now includes those who complete an apprenticeship in any form of media - from newspapers to radio to television. In a gratuitously crowd-pleasing addition, any teacher found in the audience will be hauled up on stage and ceremoniously dunked in the bucket. This ceremony used to be one of many different events - but in 2005 they scrapped the jousting competition that they held in the middle of the Rhine. Other than these main events, the festivalis a fairly typical German city festival, sort of like what Oktoberfest used to be. One high point is the overly amazing used book fair - I could have spent way more time there looking through all that they had to offer - from antique maps showing Hannibal's march over the Alps to an 1850's printing of Plato's Phaedrus for Greek students to good, cheap copies of classic German novels. If the books got to be too much, you could recuperate with the dozens of wine stands and listen to cover bands playing classic rock (ZZ Top, Deep Purple, and a great Led Zepplin cover).

In addition to rides, food and drink stands, and stalls hawking a rather odd variety of wares (everything from old advertisement placards to African folk art) there was a surprising exhibition set up in front of the Gutenberg Museum - a delegation from a traditional printing workshop in South Korea set up an interactive display where you could make paper, use traditional printing methods to print Korean characters onto these pages, and then try your hand at traditional book-binding techniques to turn the finished product into a book. And if all that weren't enough, the craftsmen also held regular demonstrations where they would cast the printing blocks out of molten lead - I was amazed at how quickly they were able to produce new characters (it took about 15 minutes to make 8 new ones). It was a very interesting exhibit, and helped to ground the book-printing process somewhere in reality for me. It's all too easy to forget just how much work goes into printing a book and especially to lose touch with it's rich history and traditions - and reconnecting with that process is what Johannisfest (at least partly) is supposed to be about.

It's that time of the semester again, and the students here in Marburg are protesting as part of a country-wide campaign under the slogan "Solidarity and Free Education." Normally these demonstrations don't really affect me, but I find them amusing. However, today they decided to "occupy" one of the buildings in which lectures are given (Oh no!) and this piqued my curiosity. I assumed that this protest was a continuation of those from earlier, but their goals have greatly expanded. Their methods have expanded too - they've led protest marches and upped their graffitti campaign dramatically. Indeed, they've gone so far as to make a list of demands, which they have printed out on flyers and are handing out all over campus.

- The demands are:

- Reformation of the Bachelor/Master degrees and modular programs of study. No admissions restrictions and more freedom within the major through individual planning and topic choice.

- Entitlement to a Master's Program if you plan to continue your present course of studies.

- Provision of necessary financing from public sources (instead of cutbacks or corporate sponsorship; at least OECD-Standard).

- (Re-)Democratisation of the universities.

- Better pay and a (secure) labor contract for all student workers (also those who work outside of the university).

- Preservation and construction of self-governed student structures.

- No survillance at universities, neither electronic or through attendance lists or something similar.

- Annulment of the "Order Paragraphs" from the Hessian law governing universities.

I can sympathize with some of these demands - specifically the demand for more freedom within their program of study. German universities operate very differently from American universities, in that you are accepted to a specific program, not a specific school. So, if after your first year you decide that you like to switch from, say, biology to chemistry, you would have to reapply - and it's highly likely that you'd end up somewhere else. In addition, there is no real way to obtain a liberal arts education - you are expected to take only courses within your subject, so getting a broad education, the goal of many American universities, doesn't even enter into the picture. Self-government and freedom from surveillance are perfectly understandable and I agree 100% with these goals - we should trust university students, especially with such demanding entrance requirements, to run their personal lives as they see fit.

Although I have some sympathy for some of these demands, others are just ridiculous. Take the "entitlement to a master's program" - if this demand were accepted, then anyone who wants to continue into a master's program, regardless of academic merit, would have to be accepted. If you combine this entitlement with the dismal budget situation at the universities, you'll quickly flood the school with underqualified candidates who use up the very limited resources - there are only so many professors that can supervise quality work at the graduate level, and straining this system will not benefit anyone. Wanting to get rid of attendance lists is absurd - since so little homework is assigned, attendance in class is necessary for participation in the course (and for, you know, learning and stuff).

There are also quite a few rants against capitalism and "corporations" but railing against these rather poorly defined entities is just par for the course in these protests. However, the clear picture doesn't really emerge until you put all of the demands together. When you do this, a few main points stand out.

First and foremost, they want a free education financed by the state (since they will pay taxes later, it's essentially a deferred loan, but they haven't seemed to pick up on this yet). Second, they want to right to study what they want for as long as they want (right to a master's program, no admissions requirements). Third, they want as much oversight removed as possible (no attendance lists, self-government). That's quite a scary package - they're asking the government to fund them indefinitely and on top of that they don't want the government to have any control over what they do. It's well and good to issue a list of demands, but if they're not willing to compromise it will be very difficult for the students to reach a solution. If they want to keep a free education, they may have to pay for it with limited options - and if they want unlimited options, they may have to pay for it themselves.

As much as I disagree with many of their demands and even how they are going about it, I respect their drive to attempt to reform their educational system from the bottom-up. I'm sure that within a few years they will reach a solution, and I'm very curious to see how it works out, and especially to discover what the students value more - cost or academic freedom.

Amsterdam is an odd city. I wasn't sure what to expect, and the city somehow managed to confirm every stereotype I had - but at the same time reveal how superficial these stereotypes really are. Yes, we saw a windmill, but it was obvious that it hadn't been used for at least a century and had been converted into a microbrewery and was clearly a local favorite, not least for its tasty and potent (8%!) wheat beer. Bikes were everywhere, but I think that that's more a function of the fact that the city is flat (they used to use the water level in Amsterdam to define sea level) and that the streets are far too narrow and crowded to risk taking a car, and the fact that the city is just spread out enough where walking isn't really an option.

Another great example is the infamous "coffeeshops" (quick side note - marijuana is not legal in The Netherlands, the police just have a policy whereby they do not prosecute you for possessing small quantities. Interestingly, they prosecute so rarely that prosecution of individuals is viewed by the courts as discriminatory and unreasonable.) - sure, there are a lot of them, and yes, you can buy weed openly - but you don't see any Dutch people in them. They're mostly full of tourists (it's a safe guess when the only thing you hear when you walk by is loud English accents), and many Dutch would like to see them shut down, or at least moved out of the city center.

Yes, there are also a lot of canals - but these aren't just pretty waterways to build the houses next to, they see quite a bit of use from the locals, who drive up and down on sunny days in all sorts of boats (we even saw one that was steam-powered!). It's a city of surprising contradictions - where else can you find Anne Frank's hiding place and the Red Light District (like the coffeeshops, it's difficult to find a native there)? The Anne Frank House was probably my favorite part of the visit - although I hesitate to use the word "favorite" with such a haunting exhibit. It's one of the most moving museums that I've visited and the staff did an excellent job recreating the "feeling" of the secret house while keeping enough humanity in the exhibit to prevent shock.

Even my hostel had a split personality - it was Christian (of the evangelical sort) right in the middle of the Red Light District, and clearly used mainly by those for whom the doctrine of forgiveness is most certainly a Good Thing. The hostel made me fairly uncomfortable (I don't like any sort of extremism in faith), but it was only for a night and I survived.

In another odd coincidence, I bough more food to take home from Amsterdam than I have anywhere else - cheese (of course, but it was sheep's cheese with herbs for cheap!), syrup cakes (they taste wayyyyy better than they sound), and of course some of the amazing beer from the windmill brewery. All in all, Amsterdam was great - I'd really like to go back - from climbing on statues to the Van Gogh Museum to just wandering the city and stumbling across its very odd corners (so many bookstores...) with a quick detour to use my Dutch (with fair, if not great, success), there's a lot that the city has to offer, and, like always, should you find yourself in the area, it's worth going well out of your way to visit.

With the ever-increasing use of medial imaging technology, such as CT scanning and MRI, it is now fairly common for tumors to be detected incidentally - that is, before they start to cause pain or produce symptoms on their own. While this incidental detection is a Good Thing (certainly better then only discovering a tumor after it has metastasized), in the case of small renal masses (tumors <4cm) - which can be either renal cell carcinomas (kidney cancer) or benign - the best way to treat these tumors is still a matter of (very) heated discussion. Standard procedure used to be a complete removal of the kidney - after all, we each have two, and if you remove the kidney you're guaranteed not to leave any positive margins. However, some recent studies have shown that mortality increases after a kidney is removed - even from factors not related to normal renal function. Consequently, there has been a trend towards removing part of the kidney in order to preserve renal function. Surgical intervention is an inherently risky undertaking, and despite what medical TV shows would have you believe, the average patient is not a young, attractive, generally healthy person - they are often elderly with many other comorbidities, such as heart disease. In these patients, the surgery can often be more traumatic than the disease itself.

The ideal treatment in these cases would be minimally invasive and tailored to the type, location, and size of tumor. In other words, if the tumor is benign, it doesn't make too much sense to remove it - but you often can't tell if a tumor is malignant or benign from a CT image, so you have to remove it or take a biopsy. If the tumor is malignant or high-grade (or even has the potential to become a nasty one) then it would be good to destroy it as effectively and as minimally invasively as possible.

Focal therapy attempts to answer some of these questions and it approaches the problem from two angles: the first is imaging (it's very hard to treat small tumors if you can't see them), and the second is therapeutic. The field is still controversial (most of the work I will talk about here is pretty far outside the current mainstream - if you don't believe me look at what the AUA has to say about ablative therapy) and it's still very much in its infancy. There are simply not enough data, but the research is quite exciting and the field holds huge promise. Ideally, we would like to be able to image a tumor, determine how serious (i.e. what grade) the tumor is, and preserve as much renal function as possible while sparing the patient from unnecessary stress (i.e. invasive procedures).

The ultimate in minimally invasive therapy is doing nothing - watching and waiting to see how the tumor progresses. However, growth rates don't correlate with tumor grade, so you can't distinguish a fast-growing benign lesion from a slow-growing malignant one. Next on the list are specifically targeted drugs - there is no surgery and they (in theory) only target the tumorous cells. However, there are not any approved drugs (but there are many in development) which accomplish this goal. After drugs, we move into surgical techniques - and the most accepted of these is a laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (removing part of the kidney). However, since this procedure is invasive, if a patient has multiple comorbidities it can cause severe complications. What's really needed is a step in between drugs and surgery - ablative therapy. Ablative therapy uses extreme cold (cryoablation) or extreme heat generated by radio waves (radiofrequency ablation, or RFA) to kill tumor cells. The effectiveness of these treatments remain unclear, but the idea is great - you can stick a needle through the skin into the kidney, check the placement of the needle with CT, and kill the tumor without ever cutting into the patient - and they can usually go home the next day!

My research over the summer (and what I presented on) focused solely on cryoablation - and the more we discover, the more questions we have to answer. The optimal parameters for cryoablation are still unclear (How long do we have to freeze the tumor for? How cold does it have to get? How can we find out if the cells are actually dead? Is using one needle or three needles a better treatment? What does the 5-year survival look like compared to other therapies?), but it was great to see the massive research effort that is going towards answering these basic questions. At the conference, I was constantly amazed by the caution, deliberation, and attention to detail surrounding every seemingly minor point - all to ensure that patients are treated in the best way possible. I learned a lot from the conference, and am shocked by both how much we know and how much we still have to discover in this field.

Yesterday was a fairly big day for me (but also a disappointment) - I gave my first poster presentation at an international conference (fancy, I know), and while there were only six other people (that's what I get for presenting basic research at a medical conference, the other rooms had 30-50 people in them), the presentation went well. Given that there were so few people, I felt kind of let down that I had practiced the talk so much, but all things considered, it's good that my first presentation was fairly gentle (i.e., no-one tried to stick me with too many difficult/impossible questions). So what am doing at a conference? Last summer I had the privilege to work in a medical research lab at UCI, and some of the work we did there was accepted to the conference "Focal Therapy and Imaging in Prostate and Rectal Cancer." Since the conference was in Noordwijk (near Amsterdam), I asked my PI from the summer if I could attend and present one of the posters, seeing as I was already in Europe and all. Fully expecting "No," I was suprised to find that not only did he say yes, but he thought that it would be a good opportunity.

The conference itself is different than I had expected - the first thing that jumped out at me is how much advertising and corporate sponsorship there was. After speaking with others with more experience than I (not hard to find!) it seems that this situation is fairly unique to European medical conferences, as such direct sponsorship is seen as a Bad Thing in the US, for better or for worse. Most of the time, however, is spent listening to leaders in the (admittedly niche and not yet mainstream) field of focal therapy (using extreme cold, radio frequencies, and radiation therapy to kill cancerous cells in a minimally invasive manner, i.e. "focused" on only the tumor itself) talk about advances. This workshop is giving me a skewed view of what urologists actually do - the procedures that we discuss here (and the research that I did) have not yet become the standard of care and are used mainly in patients whose cases are too complicated to perform traditional surgery (i.e. that kind of stress might kill them), but the great hope is that these minimally invasive techniques will find a broader use.

Today promises some really great events - all of which focus on renal cancer (and consequently the only day I'll have a chance of understanding a good majority of) and we even have the opportunity to see some of the most recent techniques used in two live surgery demonstrations - beamed in from operating rooms of course.

The conference venue (for some reason billed as Amsterdam) is a small resort town on the North Sea (at the opening ceremony the mayor hailed it as "the most prestigious [sic] beach resort on the North Sea" and while this might be (is) going just a bit too far, the town is nice, if a little small, and my room overlooks the ocean, so it's very hard to complain. I've even gotten to use my (extremely bad) Dutch to successfully order food.

Sadly, the much vaunted "100km in 24 hours" went poorly. I only made it 22km and had to stop after averaging a blister every 2km (when they get as big as silver dollars, there's a problem) and when my feet started bleeding in four places. That all sounds like complaining, and it partly is - a lot of it is indeed my fault. I'm thinking mostly of my choice of footwear, namely, why I thought that hiking sandals were a good idea to start the walk in. Don't get me wrong, I love my sandals, and they've carried me up to 15km at a stretch with no problems. Darkness and unsure footing conspired against me though, and when my feet started to slide and a hot spot developed, the game was over. Since I'm not a complete idiot, I did pack other shoes - but I couldn't get to them until station 3, at km 30 (just 8km too far!).

I won't be so bold to say that if I didn't have foot problems I could have made the whole walk - shortly after I threw in the towel it started to rain, and it kept raining for the next 6 hours - not exactly ideal conditions. And while I wasn't sore from the walk, I had only made it to slightly over 1/5 of the total and trying to extrapolate from the first part (always the easiest) is just an exercise in futility. I am, however, proud that I made the first 22km in slightly under 4'30" - not bad, and assuming (note that that is the operative word there) that I could have kept that pace up I would have been ok. While it didn't go as well as I'd hoped, it was still a great experience - watching the sun come up over a deserted mountain valley in silence was amazing - and given the possibility, I'd like to try it again - this time with real shoes.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed