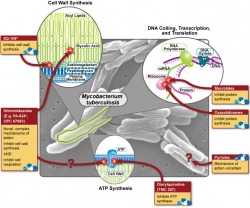

The Office of Public Health Practice hosted their annual symposium on Wednesday, and the theme was "Can the World be TB Free"? I only had a chance to attend one of the talks (by Dr. Joseph McCormick), which dealt with the rising problem of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and how our treatment strategies of TB may have helped this new disease to emerge. In what is sadly a familiar story for many bacterial diseases, the discovery of streptomycin (the first antibiotic that was effective against TB) was hailed as the first step in the elimination of the disease, but as time as passed the drug has become less and less effective, forcing us to search for new treatments. In the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, TB has exploded and the growing problem of antibiotic resistance makes treating these people very difficult. So why does drug resistance happen, and how is it our fault? There are about 10 million (or 10^7 if you're feeling scientific) individual tuberculosis bacteria living in each cavity. About one bacteria out of every 10-100 million will randomly develop a mutation that confers resistance to any one of the two major first line drugs, rifampin and isonazid. These mutations are quite rare, but given that bacteria are nothing if not effective reproducers, it is safe to assume that approximately one bacterium per cavity is resistant to rifampin, and that another is resistant to isonazid. This situation may not sound all that bad, but consider what would happen if the patient were to be treated with rifampin alone - every single bacterium would die except for the one that had developed resistance. This bacterium is now presented with perfect growth conditions - no competition and lots of food - so it begins to multiply, and after a few days have passed, 10 million bacteria live in the cavity again - but this time all of them are resistant to rifampin. Given the large number of bacteria involved, it's now reasonable to expect that one of these resistant bacteria will then develop a resistance to isonazid, and following another single-drug treatment cycle, MDR-TB is born.

4 Comments

So what exactly is public health? If you've ever wondered about this question, you're not alone - the Association of Schools of Public Health realized about a year ago that most people don't really have any idea what public health professionals do, so they made this handy website and the video below. (Link to the video in its original context.) One of the coolest parts of this campaign: you can get the stickers for free!

I like the idea of the ASPH's campaign and think it's great that the video shows a lot of public health's "hidden" aspects, but I wish that the video would show some of the dramatic effects that public health has had on society. While public health is a very broad field, it doesn't include everything (although it's a fun game to try to find some connection to public health in everyday objects - think "Six Degrees of Separation" for public health dorks). The best example is smoking - once it became clear that tobacco smoking was a major health hazard (from epidemiologic research), programs to help people quit started (thanks to Health Behavior and Health Education), and eventually policy changes were made (courtesy of Health Management and Policy) so that smoking is now banned in public places in most states (MI recently passed such a law). Other examples of changes made by public health professionals are as basic as the regulation of drinking water and ensuring that our food supplies, especially meat, remain disease-free. Going back to infectious diseases, the national vaccination program has eliminated almost all of what were formally the "childhood diseases" - no-one born in my generation has had to experience widespread polio, measles, or whooping cough outbreaks. (A list of the 10 greatest public health achievements is found here). So as a tool for raising awareness, the video is great, but I hope that it encourages people to look deeper into public health. There really is something for everyone in this field, from microbiology nerds (like me) to policy wonks (how else would we get public health laws passed?).  Last weekend I visited the University of Michigan Museum of Art as a way to escape work, classes, and the dreary weather for a few hours. I mostly visited out of curiosity (to be honest, I wasn't expecting too much from a university art museum), but I was surprised by the diversity of their collection - it's got everything from copies of Greco-Roman statues to Buddhist sculpture, with American landscape paintings and German Expressionist prints thrown in for good measure. While the main exhibits were impressive, my favorite gallery was an exhibition on Chang Ku-nien, an artist who trained in classic Chinese landscape painting in the 20th century. Following the cultural revolution, he fled to Taiwan and he was the first to paint Taiwanese landscapes in the traditional Chinese style. In his later years, he traveled extensively throughout the United States and eventually settled in Michigan, where he began to paint the landscapes of the Upper Peninsula in the traditional Chinese style (see the image below). You can find a link to the exhibition with more examples of his work here. It's not related to public health (well, I could probably find a connection if I really tried...), but the university's art museum represents one of the University of Michigan's great advantages - it's size. The sheer size of the university has two primary consequences: it can have excellent programs in many fields, and it draws world-class speakers (Kenneth Cole and Paul Krugman spoke at UMich last term). For students, the benefits are pretty obvious (free access to the vast majority of these events) and the diversity of the faculty mean that it's never difficult for a student to find an expert. The faculty, at least the ones with whom I've had contact, are willing to help even if you're not from their department. As an example, I'll need to get training from medical school faculty in order to carry out my internship this summer, and to get that training all I have to is walk down the street.

It's hard to believe that I've completed 25% of my MPH here at the University of Michigan - time has flown by since I started the program. As short as the semester was, our winter break was much shorter (they give us all of two and a half weeks off) and now it's back to work. Seeing as it's the start of a new year and all, now is a good a time as any to look back on last semester, see what I've learned so far, and look ahead to where I hope to be at the end of this semester. To be honest, I wasn't quite sure what to expect when I started last semester (it's not as much like The Hot Zone as I'd hoped...). All in all, it was much more math-based than I thought - I was expecting more of a focus on science and biology. I'll be continuing that trend this term, as most of my courses are either statistics, study design (scientific thinking combined with applied statistics), or using math to model infectious diseases (which is much more fun than it sounds, I promise). So what did I accomplish last semester? There's a picture of the workload below (it's about a foot high). While it looks like a lot, I enjoyed (almost) every minute of it. The assignments were practical and interesting, and the vast majority of the readings were enjoyable. I'm very pleased with the program so far and looking forward to another semester.

As if the stress of midterms weren't enough (it's the middle of a rather disheartening 7-week season with 1-2 tests per week), it's time to start looking for my summer internship. The department of epidemiology requires completion of an internship to earn your Master's Degree, and the great internship opportunities, especially those abroad, were one of the reasons that I came to UM. One of the hardest aspects is choosing a realistic project - everyone wants to save the world, but there's only so much that you can do in a summer, and unless you plan well you run the risk of coming back with nothing. The coursework that I've taken so far has helped me plan out the projects tremendously - I'm now comfortable identifying what I need to accomplish and I have some ideas as to how to go about collecting the data. However, I'm also realizing how little I know and how much I still have to learn before being able to make any concrete plans.

One aspect that I've decided is that I'll be going abroad to complete my internship (while I'd like to go abroad regardless, the international health track requires that I complete the internship in a developing county, which adds a nice level of extra motivation). There are a few projects that I'm interested in, ranging from the effects of parasite co-infection on endemic Burkitt's Lymphoma in Kenya to incidence of colorectal cancer in young Egyptians. While I'm still very much in the planning process, I'm excited to get started and to being putting a project together. The semester is getting into full swing, and since I like complicating my life I've agreed to blog for the UMich SPH - I'll go ahead and post my introductory blog here as well. In the future, the content here and the content there will be very similar - I may dork out a bit more on the science on this site, and anything travel-related or unrelated to SPH will stay here, so there's still a reason to check this site. The UMich SPH blog can be found here - let me know what you think. Without further ado, here's my first post for UMich SPH.

Hi! My name is David and I'm a first year student in the International Health track in the Department of Epidemiology - it sounds fancy, but just means that I'd like to apply basic epidemiologic concepts and techniques to health problems in developing countries. I took a roundabout journey to public health. Ever since reading The Hot Zone (at far too young an age) I've had a bit of a thing for microbiology, and this interest led me to microbial ecology, where I worked with extremophiles (bacteria/archaea that thrive in odd conditions, like boiling acid) during my undergraduate studies. After completing my undergraduate degree, I worked in a German lab for a year before deciding that I'd like to use my interest in microbiology to improve people's health, and after looking into epidemiology I decided that it was the right program for me. While pursuing my MPH here at UM, I'd like to research the link between infectious disease and chronic disease - there's a lot of exciting work in the field right now, with the recent HPV vaccine as the most publicized example. HIV/AIDS is another example of this phenomenon - an infectious agent (the HIV virus) causes a chronic condition (AIDS), and the more that researchers look into the field the more connections they find. There are some amazing opportunities here at the UM SPH, but one of my big concerns is the weather - I've never lived north of the Mason-Dixon line, so it'll be interesting to see how I adjust to this whole "winter" thing. Although I'm from Tennessee (at least most recently...) I went to Pomona College in Southern California for my undergraduate degree, so I'm looking forward to getting to know the Midwest. One of the main reasons that I came to UM SPH was their international internship program. As part of my degree, I'm required to complete an internship performing epidemiological research in a developing country, and right now I'm still very much in the planning stages - but I'll be sharing my thoughts (and frustrations...) as I progress through developing my project and choosing an internship site. Since I'm also a bit of a science dork, I'll blog about the conferences and seminars hosted at UM SPH and some epidemiology that makes it into the news. One of the advantages of going to a larger university is the opportunities that the school's connections and size provide. The School of Public Health at the University of Michigan has great connections with Health Departments all over the state, and they've started a program, called PHAST (Public Health Action Support Team), to help current students get involved with some of these departments. The original idea was that PHAST would provide students in "crisis situations" - outbreaks and the like - so that the Health Departments would have a free supply of readily available labor to perform tasks that they just couldn't complete. While it sounds fancy, most of these tasks are pretty basic, like interviewing people who may have eaten a given food item to track the spread of a food-borne outbreak (even though it's almost always the tuna salad...).

While the tasks may be simple, the program is part of the Michigan Center for Public Health Preparedness (also located here at UMich), which is funded by the CDC. As such, the program is integrated into the FEMA disaster response program, requiring all of us with interest in participating in PHAST to complete some basic FEMA training. The program offers free online training to anyone who's interested, so if you think that you'd like to learn more about Youth Violence or the Effects of Radiological Agents, check out this site. Since most of the focus of PHAST is on short-term need, there are only a few deployments (we stole language from FEMA too...) per semester, but the ones that they do offer should be interesting - in the past they've been as diverse as an anthrax preparedness exercise and helping to administer a flu clinic. Needless to say, I'm pretty excited about the chance to participate in these deployments, and I hope that it will give me some more insight into what it is that public health practitioners actually do. One of the things that I really like about public health is it's broad scope: sometimes it seems that pretty much everything has some impact on health. While these influences may be non-intuitive, their effect on health can be huge. Climate change is a good example. Whatever your thoughts on the subject, global temperatures and weather patterns are changing at an especially rapid pace, and this change is likely to cause a lot of problems. The Center for Global Health here at the University of Michigan hosted a nice talk today by Howard Hu about some of climate change's possible ramifications. His research focuses on environmental health, specifically air quality, so the presentation was a bit heavy on the negative effects of fine (2.5 micron!) particles produced by burning fossil fuels (it's bad, when the atmospheric concentration gets too high, risk of heart disease increases significantly). However, he also talked about how climate change will change a lot of the factors that we take for granted - especially that certain "tropical" diseases, like Dengue Fever and Malaria will stay in the tropics.

The diseases that he focused were those that are spread by mosquitoes. If the earth warms, we expect that there will be many more warm low-lying swampy areas, and these regions provide mosquitoes with an ideal habitat. In Africa, malaria is the single largest cause of death in children under 5. More than 110 million people are currently at risk of acquiring malaria, and based on some conservative projections (it should be stressed that "projection" does not mean "this is guaranteed to happen") up to 500 million people could be at risk in the near future. Perhaps most frighteningly (for us in the US anyways) is that the American South and Northern Europe, especially along the Baltic coast, are predicted as likely habitats. It's not just patterns of malaria incidence that will be changed; a very nice recent study by Danovaro et al. in PLoS ONE determined that changing patterns in the distribution of marine snow in the Mediterranean could act as a vector for spreading bacterial pathogens. Who knew that public health might lead you to study microscopic marine algae? It's been known for quite some time that climate impacts health - the environment is one of the three key features in the classical "epidemiologic triad", but the recognition that changing climate patterns (which also occurs naturally) can have far-reaching consequences on health is new and has opened up a whole new field (literally) and possibilities for transdisciplinary research. Summer camp officially ended Tuesday, and I kicked off the new school year in style - Biostatistics at 8AM, followed by five hours of class, a quick break for lunch/reading, and then another hour and a half. While it sounds slightly terrible, I love most (still undecided about one...) of my classes - it's just about what I thought that it would be, and my professors get just as excited as I do about odd things, such as vector-borne diseases and the philosophy of science. Most of my classes are pretty big (for me at least, I'm used to about 30 per class), so I'm moderately nervous about that. But each of the core classes for me (epidemiology and biostatistics) have much smaller (about 20) lab and discussion sections, so that should make learning closer to what I'm used to.

The reading is moderately intense (about 300 pages a week) but nothing too bad, all things considered. Overall, my schedule is pretty light - on MWF I've only got an hour of class, so getting work done shouldn't be a problem. Since I've got all of this free time, I started to look into possible research projects for this summer and am having quite a hard time deciding between them. Right now the winners are Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS) in SE Asia, viral etiology of tumor formation focusing on HPV in Tanzania, or how chronic parasite infection affects overall health and relates to incidence of other diseases in sub-saharan Africa (sounds fancy, but it's really just a way of saying that I'm not sure where or what exactly I want to do yet). Trying to find a research group is harder than I expected - epidemiology doesn't have as many "wet labs" (places where I can do MoBio), and unless you have a very specific study in mind, getting funding is also difficult. To develop these studies, I'll be stuck reading lots (and lots) of papers, dissertations, and grant proposals - which is very nice in that I now have a much better perspective on what it is that I'll actually be doing here. Ann Arbor is a nice college town - kind of like Marburg but without a castle on a hill and (lots) more bars. The graduate students are pretty separate from the undergrads, so the class dynamics are much nicer - everyone is just there to learn and no one wastes time asking if things will be on the test. So now I'm hoping that the workload stays pretty manageable and looking forward to a very interesting first term. Following two days of orientation (nothing too fancy and mostly involving sitting in large rooms with large groups of people), the School of Public Health gave us the opportunity to take a "practice plunge", which involved a visit to the Detroit Department of Public Health and then some volunteer work with The Greening of Detroit. The experience was a good one - although I'm a public health student I still don't know what happens on a day-to-day basis at a health department - and the sheer scale and scope of the public health department was shocking. With over 550 employees, the Detroit Public Health Department is responsible for the health and wellness of Detroit's 900,000 citizens - and "health and wellness" spans a large area. The department's interests range from providing immunizations to animal control (rabies prevention), with community outreach and education programs, free clinics, and drug abuse prevention thrown in for good measure. This spectrum of activities requires an equally broad workforce, and the department employs physicians, epidemiologists (we were offered a part-time job until they realized we didn't actually know anything yet...), and social workers. Sadly, the economy has forced the department to make dramatic budget cuts (they used to have 800 employees), which makes it very difficult to provide these necessary services to an underserved population.

The second part of our day, working on a community garden, was eye-opening. Detroit is a dying city. It has approximately one-half of it's peak population, and there are districts which abound with abandoned houses and empty lots. One (very idealistic) urban planning proposal wants to rebuild these vacant lots as community farms, and consolidate Detroit into a collection of "villages", each surrounded by (at least something approaching) farmland, modeled on (no, I'm not making this up) the English countryside. Although this grand project might not be feasible, the progress that they have made has already produced some benefits, in that they've turned an empty lot into a 26-acre park with a playground, soccer fields, and a community garden (I spent the afternoon mulching and trenching this...), and picnic tables. From what I could tell, the families in the area use the park frequently, and they enjoy it. Since it is a community projects, the locals came out to help as well, and this sense of community ownership keeps it pretty well maintained. Interestingly, these gardens connect to public health by providing a source of fruit and vegetables (like most low-income areas, fast-food restaurants outnumber grocery stores) and they have been shown to make the community safer. |

Somewhere Else

RSS Feed

RSS Feed