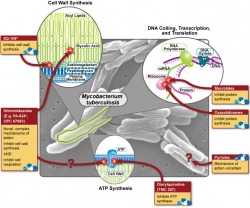

The Office of Public Health Practice hosted their annual symposium on Wednesday, and the theme was "Can the World be TB Free"? I only had a chance to attend one of the talks (by Dr. Joseph McCormick), which dealt with the rising problem of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and how our treatment strategies of TB may have helped this new disease to emerge. In what is sadly a familiar story for many bacterial diseases, the discovery of streptomycin (the first antibiotic that was effective against TB) was hailed as the first step in the elimination of the disease, but as time as passed the drug has become less and less effective, forcing us to search for new treatments. In the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, TB has exploded and the growing problem of antibiotic resistance makes treating these people very difficult. So why does drug resistance happen, and how is it our fault? There are about 10 million (or 10^7 if you're feeling scientific) individual tuberculosis bacteria living in each cavity. About one bacteria out of every 10-100 million will randomly develop a mutation that confers resistance to any one of the two major first line drugs, rifampin and isonazid. These mutations are quite rare, but given that bacteria are nothing if not effective reproducers, it is safe to assume that approximately one bacterium per cavity is resistant to rifampin, and that another is resistant to isonazid. This situation may not sound all that bad, but consider what would happen if the patient were to be treated with rifampin alone - every single bacterium would die except for the one that had developed resistance. This bacterium is now presented with perfect growth conditions - no competition and lots of food - so it begins to multiply, and after a few days have passed, 10 million bacteria live in the cavity again - but this time all of them are resistant to rifampin. Given the large number of bacteria involved, it's now reasonable to expect that one of these resistant bacteria will then develop a resistance to isonazid, and following another single-drug treatment cycle, MDR-TB is born.

4 Comments

While browsing the interweb, I came across this video by Hans Rosling - probably the most amusing statistician alive today (and no, that's not an oxymoron). Dr. Rosling teaches International Health at the Karolinksa Institutet (like Harvard, but in Sweden), and is also the Director of the Gapminder Foundation. Gapminder has some more amusing videos on their site and they take health issues, like HIV/AIDS, and present them in an entirely new context. What I especially like about the site is that they recognize that the issues are complex and that simple solutions probably don't exist (you can see this at the end of the above video when he says that he supports the media coverage, but warns us not to read into it too much).

After a few days of lounging on the beach and reading, we decided to explore the island of Maui in a bit more depth (lounging around is nice and all, but I tend to get a bit stir crazy after a few days). I hadn't gotten the chance to go diving in over a year (it seems like a lifetime ago when I was in the water at least twice a day on the weekends) so when I had the opportunity I jumped at the chance. The site of my first dive after the hiatus could not have been better - a shallow reef inside the remains of a volcanic crater. While it was nice to be underwater again (I was surprised at how quickly my buoyancy control came back to me), the clear highlight of the dive was listening to the humpback whales underwater. The crater is shaped like a half-moon, and the hard rock walls amplify and reflect all the sound that comes into it, making it one of the best underwater spots to hear whales singing. And it wasn't just underwater that we found whales - they are everywhere around Maui this time of year, and we saw close to a dozen on the boat ride between the harbor and the dive site. Sadly, none of them breached, but you can't have everything...  The day after the dive trip (which turned out to be more chaotic than I'd have liked - my dive computer flooded and I almost left my camera on the dive boat...), we found ourselves with access to a rental car, thanks to the arrival of my friend's sister. The weather was not outstanding as we drove around the island (in case the giant crashing seas in what is supposed to be a tropical paradise didn't give that away), but we made the best of it and trekked to blowholes, swimming holes, and the best banana bread stand in the world. Getting to the banana bread stand was the hardest part - although we had to climb over lava rocks to get to the swimming holes, getting to the banana bread stand required a fairly long drive up one-lane cliffside road, with a good amount of traffic moving in both directions. The village that the banana bread was in was worlds apart from the resort complexes that most people think of when they imagine Hawaii - it was a very rural and economically depressed area, and it didn't look like many visitors made it to that part of the island. Sadly, there was one major disappointment of the trip. We woke up at 3AM to go watch the sunrise over a volcanic crater, but the weather conspired against us - after two hours of standing in a cloud/fog bank/something cold and very damp, all that happened when the sun rose was that the cloud turned from black to a lighter shade of dark gray. Inspiring it was not, but now I have a reason to go back. Following the mountain adventure, we headed down to Pa'ia to sit on the beach for one last time, and then it was off to the airport to fly home to Michigan. When I made it back, there was still snow on the ground (which has thankfully since melted). For more pictures, you can check out the gallery here.

So what exactly is public health? If you've ever wondered about this question, you're not alone - the Association of Schools of Public Health realized about a year ago that most people don't really have any idea what public health professionals do, so they made this handy website and the video below. (Link to the video in its original context.) One of the coolest parts of this campaign: you can get the stickers for free!

I like the idea of the ASPH's campaign and think it's great that the video shows a lot of public health's "hidden" aspects, but I wish that the video would show some of the dramatic effects that public health has had on society. While public health is a very broad field, it doesn't include everything (although it's a fun game to try to find some connection to public health in everyday objects - think "Six Degrees of Separation" for public health dorks). The best example is smoking - once it became clear that tobacco smoking was a major health hazard (from epidemiologic research), programs to help people quit started (thanks to Health Behavior and Health Education), and eventually policy changes were made (courtesy of Health Management and Policy) so that smoking is now banned in public places in most states (MI recently passed such a law). Other examples of changes made by public health professionals are as basic as the regulation of drinking water and ensuring that our food supplies, especially meat, remain disease-free. Going back to infectious diseases, the national vaccination program has eliminated almost all of what were formally the "childhood diseases" - no-one born in my generation has had to experience widespread polio, measles, or whooping cough outbreaks. (A list of the 10 greatest public health achievements is found here). So as a tool for raising awareness, the video is great, but I hope that it encourages people to look deeper into public health. There really is something for everyone in this field, from microbiology nerds (like me) to policy wonks (how else would we get public health laws passed?).  Last Friday, I left 1 1/2 feet of snow on the ground in Ann Arbor and headed to Maui for spring break (it's a rough, rough, life). It was a transition in more ways than one - I was not even close to ready for the 60 degree temperature increase or the fact that I suddenly found myself with the free time to sit down and read a book (4 down so far). The week started off with a somewhat overhyped tsunami warning (all that happened was that we were confined to our hotel for a few hours), but even tsunami warnings are enjoyable in the Aloha state - from the balcony we could see humpback whales breaching in the distance. The scenery is also a nice change from Hawaii - rainforest-covered mountains are a far cry from the flat and snowy midwest.  But after a week of lounging, scuba diving, and accidental whale-watching ( humpbacks seem to pop up everywhere here) I'm excited to get back to work. Epidemiology seems to have worked its way into my head and I keep finding odd connections and epidemiologic puzzles, even while on vacation. The best example of this comes from sea turtles, of all places. While snorkeling, we saw a sea turtle that had 5-6 baseball sized tumors on it's neck, flippers, and tail. Curious as to what caused the tumors, I've been asking around but it appears that everyone is stumped (even scuba instructors, normally a source of good info - or at least willing to make something up as long as it's interesting - also didn't have a clue). Like any good scientist, my first thought was to turn to google. After a few minutes of intense digging (it is still vacation, after all) I found this site. From a modest beginning with only a few sightings reported in the 1960's, it is now believed that the disease afflicts more than 60% of Hawaii's green turtles and is sadly often fatal. Although the cause remains unknown, one theory is that the disease is caused by a virus and that it will soon reach epidemic proportions in other sea turtle populations. Now if only I could convince UM SPH to let me study that outbreak...

|

Somewhere Else

RSS Feed

RSS Feed