It's hard to believe that Fall Break happened over a week ago - with midterms, problem sets, and the poster session, time has been flying by here at SPH. Thankfully, Fall Break this year was actually a break (last year all of the midterms were after the break, so it was more of a "break from class so you won't be distracted while you study" type of a vacation), so I figured that I'd use the time to go explore Michigan. The area around Ann Arbor is nice - lots of rivers, streams, and lakes - but I'd never seen the northern half of Michigan and so decided to camp at Sleeping Bear Dunes for a few days. The weather was perfect - high 60s and sunny - and since it was the middle of the Fall, the campsites were fairly empty (at least we didn't have to contend with lots of loud RVs at night). We also managed to hit that point right before the leaves drop off the trees, so the drive north to Traverse City (only about 4 hours) had lots of nice scenery along the way. The camping was different than I'm used to (there was actually running water and permanent toilets!), so "roughing it" isn't really an apt description of the facilities. The park has lots of nice trails that wander through the dunes, and it's easy to forget that you're standing on sand that was dropped here at the end of last ice age when you're walking through the middle of a forest. Once you make it through the dunes, the views out over Lake Michigan and across to the Manitou Islands are great. There's even a dune climb where you can hike up the hills for a bit and over to the lakeshore (although running down on the trip back is more fun...).  This trip was my first time seeing one of the Great Lakes, and it was weird to see waves in something that didn't have a salt spray. The more I explore Michigan, the more I come to like the state - it's much different than I had expected when I moved here, and there's lots of state parks and forests to explore. All in all, the trip up north was a great way to escape school and homework for a few days, and it's inspired me to plan a trip to the Upper Peninsula sometime next year - after the snows melt, of course.

3 Comments

Modern research endeavors rely on the power of computers to perform complicated analyses, and drug discovery projects are especially computation intensive. Although most researchers have access to powerful computers, getting time on them is difficult (it's pretty much guaranteed that any researcher will have to compete with physical chemists, climatologists, astronomers, and a host of other scientists for these machines). Fortunately, minds smarter than I have come up with an interesting solution to this problem that relies on one simple observation: the computer that you're using to read this article is actually a pretty powerful machine, and most of the time you don't use it to it's full capacity (especially when it's sitting idle on your desk...). Your computer can then be linked to a series of other computers and used to help work out complex calculations in its spare time.

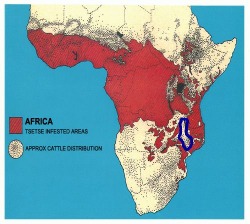

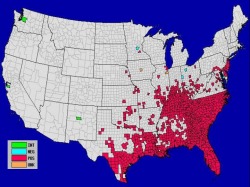

Distributed computing may seem like nothing more than a nice addition to more traditional research methods, but a project looking for novel treatments for neuroblastoma, a type of childhood cancer, found that using this distributed grid would cut the time required to finish the calculations from a staggering 8,000 years down to 1-2 years. One of the most appealing aspects of the World Community Grid is that it allows you to choose the projects to which you'd like to donate your computer's spare time. Most of them have a fairly direct relation to public health. New treatments for dengue fever are obvious, as are projects looking to improve access to clean water, but a project studying novel ways to predict African climate may seem like it's not the highest priority at first. However, weather affects mosquito ranges (and thereby the future spread of certain diseases) and which land will become non arable in the future - and food security is a major issue in public health. The grid keeps detailed statistics for the projects you've participated in, and allows you to join "teams" that pool all it's members together to earn points (you can't do much with them but competition makes things more fun). You can join the UMich ESO team by clicking here (those from other departments/institutions are also welcome, but should you feel so inclined you could start your own team and challenges may ensue...). Best of all, it's a way to help advance science in your spare time - without having learn any of the detailed biology or math. On opposite sides of the world in 2009, two vector-borne diseases that we thought were under control - dengue fever in the Florida Keys and Human African Trypanosomiasis (AHT, more commonly known as African Sleeping Sickness) in northern Malawi - returned. AHT is one of the most dreaded tropical diseases, with good reason - it is invariably fatal in the absence of proper treatment. Over 60 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are at risk and 50,000 die each year. The main vector of AHT is the tsetse fly, and control efforts have focused on eliminating this insect from endemic regions. During the 1980's and 1990's, a successful vector control program virtually eliminated the tsetse fly from Malawi, but as the disease burden decreased, funding stopped and now it appears that they fly has returned to northern Malawi. The return of the tsetse fly isn't just bad for humans - the fly can also carry a trypanosome that fatally infects cattle, which has a severe impact on the local economy. The economic impacts can be just as devastating - a Malawian villager reported, "Our colleague last year lost almost all his cattle totaling 30 head and remained with only two. We are worried because everybody is losing livestock. The flies are bringing poverty here." Dengue fever - also known as "breakbone fever" for the severe pain caused by the first infection - is the most common vector-borne viral disease worldwide. The first infection is rarely fatal, but there are four different dengue serotypes. Infection with one serotype confers immunity to that serotype, but if someone who has already been infected with one dengue serotype is infected by a different serotype, dengue hemorrhagic fever, a life-threatening illness, can result. In May 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the first locally acquired case of dengue Fever in the United States since 1946 - and that there had likely been an ongoing outbreak of dengue in the Florida Keys since 2009. A serosurvey found that up to 5% of all Florida Keys residents have been exposed to dengue. Yes, you read the first part of that sentence correctly - we eliminated dengue from the United States when we eliminated malaria (both using vector control strategies) in the mid-40's, and now it's back. The Florida Keys are a major tourist destination, and the main fear is that dengue will spread from the Keys to the rest of the United States when travelers return home. Many of the mosquitoes in the United States are capable of transmitting the virus, so the possibility of spread is a real concern. The map below shows the distribution of Aedes albopictus, one of the main vectors of dengue, in the United States. It is present in all of the counties in red, and absent from those in blue. Gray counties represent those that the Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases (DVBID) didn't have the necessary funding or manpower to survey. These two outbreaks follow the same pattern - successful vector control programs resulted in the elimination of a deadly disease, and the success of these programs led many to conclude that they were no longer necessary. The problems posed by these two outbreaks are similar, but the official responses couldn't be more different. In Malawi, the return of the tsetse fly was front page news for the Sunday edition of the national paper, while news of the dengue outbreak in the United States was somewhat more difficult to find (the New York Times ran a nice article on the subject). The Malawian government and local officials have discussed the outbreak openly, asked for help, and are proposing to fund a control initiative. In contrast, the United States has imposed severe budget cuts on the CDC, forcing the closure of the DVBID (the same division that warned us of the problem), and health officials in the Keys are denying that dengue is a problem. Which country's policies seem more sensible?

More on the dengue outbreak can be found at: White Coat Underground TIME The World Cup is in full swing and although the only remaining African team was knocked out by the most blatant display of poor sportsmanship I think I've ever seen, it's still the most popular event on TV and one of the main topics of conservation here in Blantyre. For many Malawians, the World Cup may be the only TV event that they have seen in a few months and they may not see another TV event for a while ("exciting" is not a word I'd use to describe the regularly scheduled programming on Malawi's only TV station). Public health officials are taking full advantage of this situation and a constant feature of the broadcasts is a small band of text at the bottom of the screen encouraging the viewers to use the mosquito nets and visit the health clinics if they suspect that they or a family member might have malaria. To drive the point home, the half-time analysts usually wear shirts with the local "Roll Back Malaria" logo.

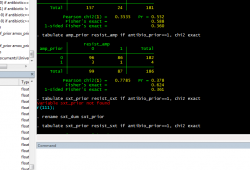

Malaria is a major problem in Malawi - it's not uncommon for a child to suffer from the disease 4-5 times in a single year and it is one of the leading causes of mortality in children under 5. Although there are some effective preventive measures and treatments available, people must visit a clinic before they take advantage of them. Visiting a clinic can be expensive - the visit itself is free, but the wait can be as long as 8 hours to see a doctor, and if you have to wait that long that means missing out on a day of work. One small problem with this campaign is that the notices are only in English. Although all Malawians learn English in school, it's certainly possible that these messages would reach more people if they were also presented in Chichewa, the dominant native language. Other than this small quibble, I think it's great that officials are using the World Cup as an opportunity to bring important public health messages to as many people as possible. The day-to-day routine of epidemiology is not always thrilling. Although fieldwork and data collection are fun, once you've collected the data you have to analyze it - and before you can analyze it, you have to clean it. Before I started my internship, data cleaning was a mystery to me, but after spending 3 weeks cleaning a rather large data set I've realized that it's mostly a tedious process - going through each individual observation (there can be anywhere from a few hundred to over ten thousand) and making sure that all of the variables make sense. However tedious it is, it's one of the most important steps in the analysis. Computers are fundamentally stupid and only do (exactly) what you tell them - if that wasn't enough, they have a hard time figuring out what letters are, so a major part of data cleaning and entry is devising codes to convert your data into a series of numbers. It's not exactly the most glamorous part of research, but it needs to be done before you can start asking the questions you set out to answer. The upside of data cleaning is that I spend most of my day looking at screens like the one below: It appears that I'm rapidly approaching the end of the data cleaning and finishing up some of my analyses, and I'll be off to Liwonde for the next 2-3 weeks to start collecting data from the district hospital there. Thankfully, I'll be able to put the computer away for a few weeks and start to learn how the data that make up our datasets get collected.

After climbing Mt. Mulanje over the weekend I no longer doubt that Chichewa has 13 words for "mud" and none for "switchback." Mulanje is not a typical mountain - it's more of a giant granite mesa that juts up from the surrounding tea estates. There are over 76 peaks on top of this plateau, but getting up to the plateau requires more than a bit of effort and covering almost 2,000 vertical feet in less than 2 miles. Just when you think you're doing well, your porters will pass you literally running up the mountain in bare feet (or if they feel the need to protect themselves, flip-flops).  Once you finish the climb (after stopping every 20 minutes or so to catch your breath and enjoy the view out into Mozambique) you find yourself on a large plateau with some gently rolling hills. The landscape shares a strange affinity with some areas of Scotland, and this effect was heightened by the misty weather that rolled in every afternoon (we managed to visit during a chiperonde, which is a fancy word for cold, wet air blowing in from Mozambique that settles over Southern Malawi for days at a time). The mountain itself is an interesting place - local legend maintains that it is home to evil spirits (the name of the highest peak, Sapitwa, translates to "Don't go there.") and there are no permanent settlements on the plateau, but there are large tracts of Mulanje Cedar that the forestry department allows the locals to harvest.  We camped overnight in a hut which thankfully had a nice fireplace (temperatures dropped to below freezing soon after the sun went down) and woke up early the next morning to climb Namasile (pictured at the top), the second highest peak on the massif (and therefore in all of Malawi). The trail up the peak followed a stream bed over some rolling hills for about 30 minutes until we began the ascent - another hour of fairly uneventful steep slopes. Then we lost the trail. It happened at a large boulder that was totally overgrown with moss and trees (a very Indiana Jones-esque moment, especially when we found leopard scat in the cave we eventually had to crawl through). Apart from this small detour, the rest of the climb was uneventful and we made it to the summit just as the clouds rolled in and obscured our view of just about everything. Interestingly, the first thing our guide did was to bang a rock against a metal sign to scare the spirits away (although he claimed later that the myths were all lies told to impress the visiting white people). We made it down fairly quickly, camped overnight again, and then started down the plateau the next morning, which was certainly easier than it was going up. Once we made it down, we drove around the mountain and had lunch at, of all things, a Malawian-run Italian restaurant. Pizza and beer have never tasted so good.

Malawi has odd visa requirements - you can stay in the country continuously for up to 3 months without any problems, but if you stay longer than 3 months than you must enter a nightmarish world of bureaucracy, fines, and paperwork to obtain a 6-month permit. However, if you leave the country after three months and re-enter, you can stay for another 3 with no problems. One of my housemates found himself in this situation, so we decided to resolve the problem in the only reasonable manner: by going on safari. Malawi has a few game parks and national preserves, but none compare to South Luangwa National Park in Zambia. Getting there was a bit of a challenge - 4 hours by bus to Lilongwe, then a 6-hour car transfer from Lilongwe (Malawi) to Mfuwe (Zambia), the last 3-hours of which are on an insanely bumpy and dusty road, and finally on to the park (after a two-hour stop at the border, the particulars of which still confuse me).  We arrived in camp around dusk, greeted by Moses (our guide) with the words "Do you want to see a crocodile?" (the answer is always yes). Disoriented from the ride, we walked about 25 feet and came to the riverbank, where we could see crocs and hippos about 10 yards away from us. After this introduction we had a brief speech about safety (don't walk alone at night; too many hippos and elephants - I thought they were joking but when I was woken up at 3AM by an elephant not three feet from my tent it became clear that that might actually be a Good Idea) and then it was off to dinner. Safaris start early (animals don't wait for people) and we hit the road at 6AM (wake-up call at 5AM) for our first trip into the bush. Honestly, I wasn't expecting much and told myself that I would be happy with seeing a few elephants, some grazers, and maybe a hippo, zebra, or giraffe. I was wrong. Within an hour we had found two lions and a herd of zebra, and before the drive was over we'd also seen 12 elephants and ambushed a herd of giraffes. The night drive (4PM to 8PM) was even better - it started off by watching a pride of lions stalk an impala (they failed), and then driving to within 2 feet of the pride, where the male proceeded to mate with the females (which they told is quite rare). Video (which is funnier than it should be) will be on YouTube soon. As night fell, we focused on the one animal that we hadn't seen - a leopard. Although South Luangwa is one of the best places to see them, our guides warned us that we probably wouldn't get so lucky this time around. They were wrong - not only did we find a leopard with 15 minutes, we saw and helped it stalk an impala by using our car to provide cover. Stalking takes a long time, so we switched off the lights and sat in the dark for 15 minutes, listening to the impala bark at each other. We suddenly heard an impala bark much louder and then hooves running away, but when we switched the light back on we saw that the leopard had missed.  The camp at which we stayed was an adventure in itself - although we slept in tents, they had permanent beds and there were so few people that we each had a tent to ourselves so I'd hesitate to call it camping. Monkeys and baboons ran around the grounds at will, and woe be unto him who left food unattended for more than a few minutes (the monkeys are tricky devils). At night, hippos and elephants began their invasion, and you could count on waking up at least once a night thanks to nearby hippos, who are surprisingly fast out of the water.

The second day was just as exciting as the first - we saw more elephant herds, giraffes fighting, hippos eating, and a fantastic sunset over the river. We even managed to spot yet another leopard, although we only followed this one for a few minutes. After two days of safari, it was back to Blantyre, but South Luangwa is certainly a place I'd love to visit again.  I'll be spending my summer internship in Blantyre, Malawi, where I'll be working on a few projects. My office is in the Malaria Alert Centre, which is conveniently located next to the central hospital (where one of my advisers works) and also houses the Blantyre Malaria Project, with whom I'm collaborating on a project that is trying to develop a diagnostic algorithm to differentiate pediatric patients with bacterial meningitis from those with cerebral malaria. Both diseases have very similar symptoms and a high mortality rate, but unfortunately they both require different treatments.

Complicating the situation, many health care centers (and even some district hospitals) in Malawi don't have the resources that they need to perform even basic lab work (in some cases they are unable to determine hematocrit or blood glucose), so this algorithm would ideally be based on 4-5 clinical observations that don't require sophisticated equipment. While I'm in Malawi I'll also be collaborating on a project to determine the burden of cancer in Malawi - we take it for granted in the US that we know how many cancer cases occur each year, and what the most common types of cancer are, but that information has not been systematically collected for Malawi, which makes it difficult to allocate health care resources to where they are needed. I share my office with two other researchers - an MD/PhD studying cerebral malaria, and a post-doc working on a device to measure the size of a hole that red blood cells infected with malaria can pass through. We have a fourth seat in our office which visiting researchers and professors will often use when they need a place to sit and work. It's a humble office on the second floor that is well-supplied with tea, coke, and various snacks (including the tasty but unfortunately named "Salticrax" cracker). The office looks out over fields and the noise from people working will drift in (it's the cooler dry season and our windows stay open during the day), the MAC insectory, where they raise mosquitoes (and the reason we have to close our windows when it gets dark), and across to the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust. Combined, it's a nice view of both average life in Malawi and sophisticated research institutions, highlighting the need for research on infectious disease and the hope that research here will one day lead to better care.  Blantyre is not the world's most exciting town. The city consists of a small downtown area with some shops, restaurants, and a moderate commercial district (one to two banks) surrounded by suburbs, with a small shopping center located near the hospital. Hanging around for the weekend is not exactly the most thrilling way to spend your time. Thankfully, Blantyre is surrounded by great opportunities - there are three mountains that you can climb within 10km of the city proper, and there are no less than 3 game reserves within an hour's drive. These game preserves are off the main tourist track so when we went to visit Majete Wildlife Reserve we had the park to ourselves - we saw one other car for the 6 hours that we were there. Combine the ease of access with the low entrance fee ($20 including gas to and from the park) and it's a perfect place to escape from Blantyre. I didn't expect much from the park - it looked fairly small on the map, but as soon as we drove in my mistake became apparent. The entrance to the park is next to Kapuchiri Falls, which stopped the famous Dr. Livingstone on his first attempt to travel up the Shire River into Malawi. On our way up from the falls we had to stop the car suddenly - 5 elephants chose that moment to cross the road and start grazing about 20 feet away from our car. Violating the first rule of animal safety, I of course got out of the car to take a few pictures (totally worth it) and through dumb luck or the elephants' friendliness I escaped unharmed (although we left the door open in case I should need to sprint back into the car and drive away).  After spotting the elephants we hit a bit of dry spell (not that I'm complaining) were we saw mostly elands, impalas, and sable until reaching the "Hippo Spot", where, true to it's name, about 10 hippos were basking in the sun and sitting in the river. We carried on from this point to a loop around the park (thick underbrush does not a good chance to spot animals make) and were surprised by a massive herd of impala (60-80 strong) leaping across the road with four zebra in pursuit. The impala can jump - their hind legs go above their head and the highest point and it looks like the twisting will either break the back or force them to to tumble down, but they always seemed to land without even breaking stride.

The park was devastated by poaching in the '80s and '90s, but starting in 2006 it has been the focus of an intensive plan to repopulate the park and increase the diversity. They've successfully imported 75 elephants from Liwonde National Park, and the herd now numbers 150. There are supposedly 7 rhinos hiding in the park somewhere, but they are rarely seen. The rangers also plan to introduce lions to the park in 2012, which will be a shock to the complacent population of grazers (I hope all the elands and zebras remember how to run...) but should also bring more visitors to the park. The World Cup starts in South Africa this weekend, and excitement is building, especially here in Africa. As if that weren't enough, qualifications are in progress for the African Nations Championship and soccer fever is in full swing here. This fever is somewhat infectious, so when Angola played Malawi over the weekend here in Blantyre we jumped at the chance to get tickets and see the game. Seating was sold by three levels: open seating (no overhead protection from the sun and the rain), covered seating (you get to sit in the shade), and "VIP" seating (you also sit in the shade, but I think you are closer to the field). The weather was nice, so we decided on open seating (the fact that we are cheap may also have influenced this decision).

The stadium itself is a rather precarious concrete structure which looks as if collapse is a real possibility, but it's a very nice venue to watch a game - the open seating means that you can sit as close to the centerline as you dare (the rowdier locals, many of whom consume prodigious amounts of ethanol before entering the stadium, tend to prefer these seats as well) and the seats are close enough to the field where even the nosebleeds can get a good sense of the game. Getting into the stadium is an experience in itself, and the vendors who set up shop outside sell everything from coke to candy to small roasted birds on a stick (if you're feeling adventurous you can buy roasted mice with the fur intact). We arrived a bit later than planned and sat close to one of the goal lines, but our seats were right next to the stairs leading up the bleachers. This placement led to us "befriending" many of the aforementioned locals, who were shocked to see an azungu (friendlyish word for whitey) in the stands (not all too surprising, given that we one of 15, and 8 of them chose the more expensive seats). The game itself was interesting - Angola's players seemed to suffer from a spate of sudden injuries during Malawi's drives for the goal, although thankfully these injuries resolved themselves rapidly after play had stopped and they had been taken to the sideline. The first half saw the most excitement when Angola scored 2 goals within 5 minutes, and Malawi couldn't catch up in the second half. Although Malawi lost, where else can you watch two national teams play each other for less than $2.00? |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed