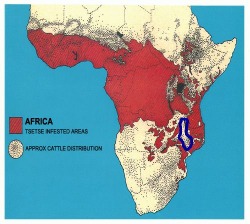

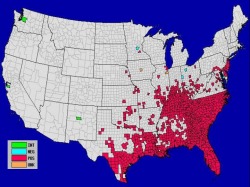

On opposite sides of the world in 2009, two vector-borne diseases that we thought were under control - dengue fever in the Florida Keys and Human African Trypanosomiasis (AHT, more commonly known as African Sleeping Sickness) in northern Malawi - returned. AHT is one of the most dreaded tropical diseases, with good reason - it is invariably fatal in the absence of proper treatment. Over 60 million people in sub-Saharan Africa are at risk and 50,000 die each year. The main vector of AHT is the tsetse fly, and control efforts have focused on eliminating this insect from endemic regions. During the 1980's and 1990's, a successful vector control program virtually eliminated the tsetse fly from Malawi, but as the disease burden decreased, funding stopped and now it appears that they fly has returned to northern Malawi. The return of the tsetse fly isn't just bad for humans - the fly can also carry a trypanosome that fatally infects cattle, which has a severe impact on the local economy. The economic impacts can be just as devastating - a Malawian villager reported, " Our colleague last year lost almost all his cattle totaling 30 head and remained with only two. We are worried because everybody is losing livestock. The flies are bringing poverty here." Dengue fever - also known as "breakbone fever" for the severe pain caused by the first infection - is the most common vector-borne viral disease worldwide. The first infection is rarely fatal, but there are four different dengue serotypes. Infection with one serotype confers immunity to that serotype, but if someone who has already been infected with one dengue serotype is infected by a different serotype, dengue hemorrhagic fever, a life-threatening illness, can result. In May 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the first locally acquired case of dengue Fever in the United States since 1946 - and that there had likely been an ongoing outbreak of dengue in the Florida Keys since 2009. A serosurvey found that up to 5% of all Florida Keys residents have been exposed to dengue. Yes, you read the first part of that sentence correctly - we eliminated dengue from the United States when we eliminated malaria (both using vector control strategies) in the mid-40's, and now it's back. The Florida Keys are a major tourist destination, and the main fear is that dengue will spread from the Keys to the rest of the United States when travelers return home. Many of the mosquitoes in the United States are capable of transmitting the virus, so the possibility of spread is a real concern. The map below shows the distribution of Aedes albopictus, one of the main vectors of dengue, in the United States. It is present in all of the counties in red, and absent from those in blue. Gray counties represent those that the Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases (DVBID) didn't have the necessary funding or manpower to survey. These two outbreaks follow the same pattern - successful vector control programs resulted in the elimination of a deadly disease, and the success of these programs led many to conclude that they were no longer necessary. The problems posed by these two outbreaks are similar, but the official responses couldn't be more different. In Malawi, the return of the tsetse fly was front page news for the Sunday edition of the national paper, while news of the dengue outbreak in the United States was somewhat more difficult to find (the New York Times ran a nice article on the subject). The Malawian government and local officials have discussed the outbreak openly, asked for help, and are proposing to fund a control initiative. In contrast, the United States has imposed severe budget cuts on the CDC, forcing the closure of the DVBID (the same division that warned us of the problem), and health officials in the Keys are denying that dengue is a problem. Which country's policies seem more sensible? More on the dengue outbreak can be found at: White Coat Underground TIME

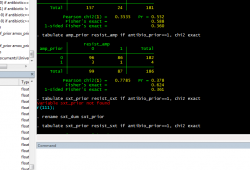

The day-to-day routine of epidemiology is not always thrilling. Although fieldwork and data collection are fun, once you've collected the data you have to analyze it - and before you can analyze it, you have to clean it. Before I started my internship, data cleaning was a mystery to me, but after spending 3 weeks cleaning a rather large data set I've realized that it's mostly a tedious process - going through each individual observation (there can be anywhere from a few hundred to over ten thousand) and making sure that all of the variables make sense. However tedious it is, it's one of the most important steps in the analysis. Computers are fundamentally stupid and only do (exactly) what you tell them - if that wasn't enough, they have a hard time figuring out what letters are, so a major part of data cleaning and entry is devising codes to convert your data into a series of numbers. It's not exactly the most glamorous part of research, but it needs to be done before you can start asking the questions you set out to answer. The upside of data cleaning is that I spend most of my day looking at screens like the one below: It appears that I'm rapidly approaching the end of the data cleaning and finishing up some of my analyses, and I'll be off to Liwonde for the next 2-3 weeks to start collecting data from the district hospital there. Thankfully, I'll be able to put the computer away for a few weeks and start to learn how the data that make up our datasets get collected.

After climbing Mt. Mulanje over the weekend I no longer doubt that Chichewa has 13 words for "mud" and none for "switchback." Mulanje is not a typical mountain - it's more of a giant granite mesa that juts up from the surrounding tea estates. There are over 76 peaks on top of this plateau, but getting up to the plateau requires more than a bit of effort and covering almost 2,000 vertical feet in less than 2 miles. Just when you think you're doing well, your porters will pass you literally running up the mountain in bare feet (or if they feel the need to protect themselves, flip-flops).

Once you finish the climb (after stopping every 20 minutes or so to catch your breath and enjoy the view out into Mozambique) you find yourself on a large plateau with some gently rolling hills. The landscape shares a strange affinity with some areas of Scotland, and this effect was heightened by the misty weather that rolled in every afternoon (we managed to visit during a chiperonde, which is a fancy word for cold, wet air blowing in from Mozambique that settles over Southern Malawi for days at a time). The mountain itself is an interesting place - local legend maintains that it is home to evil spirits (the name of the highest peak, Sapitwa, translates to "Don't go there.") and there are no permanent settlements on the plateau, but there are large tracts of Mulanje Cedar that the forestry department allows the locals to harvest.

We camped overnight in a hut which thankfully had a nice fireplace (temperatures dropped to below freezing soon after the sun went down) and woke up early the next morning to climb Namasile (pictured at the top), the second highest peak on the massif (and therefore in all of Malawi). The trail up the peak followed a stream bed over some rolling hills for about 30 minutes until we began the ascent - another hour of fairly uneventful steep slopes. Then we lost the trail. It happened at a large boulder that was totally overgrown with moss and trees (a very Indiana Jones-esque moment, especially when we found leopard scat in the cave we eventually had to crawl through). Apart from this small detour, the rest of the climb was uneventful and we made it to the summit just as the clouds rolled in and obscured our view of just about everything. Interestingly, the first thing our guide did was to bang a rock against a metal sign to scare the spirits away (although he claimed later that the myths were all lies told to impress the visiting white people). We made it down fairly quickly, camped overnight again, and then started down the plateau the next morning, which was certainly easier than it was going up. Once we made it down, we drove around the mountain and had lunch at, of all things, a Malawian-run Italian restaurant. Pizza and beer have never tasted so good.

I'll be spending my summer internship in Blantyre, Malawi, where I'll be working on a few projects. My office is in the Malaria Alert Centre, which is conveniently located next to the central hospital (where one of my advisers works) and also houses the Blantyre Malaria Project, with whom I'm collaborating on a project that is trying to develop a diagnostic algorithm to differentiate pediatric patients with bacterial meningitis from those with cerebral malaria. Both diseases have very similar symptoms and a high mortality rate, but unfortunately they both require different treatments. Complicating the situation, many health care centers (and even some district hospitals) in Malawi don't have the resources that they need to perform even basic lab work (in some cases they are unable to determine hematocrit or blood glucose), so this algorithm would ideally be based on 4-5 clinical observations that don't require sophisticated equipment. While I'm in Malawi I'll also be collaborating on a project to determine the burden of cancer in Malawi - we take it for granted in the US that we know how many cancer cases occur each year, and what the most common types of cancer are, but that information has not been systematically collected for Malawi, which makes it difficult to allocate health care resources to where they are needed. I share my office with two other researchers - an MD/PhD studying cerebral malaria, and a post-doc working on a device to measure the size of a hole that red blood cells infected with malaria can pass through. We have a fourth seat in our office which visiting researchers and professors will often use when they need a place to sit and work. It's a humble office on the second floor that is well-supplied with tea, coke, and various snacks (including the tasty but unfortunately named "Salticrax" cracker). The office looks out over fields and the noise from people working will drift in (it's the cooler dry season and our windows stay open during the day), the MAC insectory, where they raise mosquitoes (and the reason we have to close our windows when it gets dark), and across to the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust. Combined, it's a nice view of both average life in Malawi and sophisticated research institutions, highlighting the need for research on infectious disease and the hope that research here will one day lead to better care.

Blantyre is not the world's most exciting town. The city consists of a small downtown area with some shops, restaurants, and a moderate commercial district (one to two banks) surrounded by suburbs, with a small shopping center located near the hospital. Hanging around for the weekend is not exactly the most thrilling way to spend your time. Thankfully, Blantyre is surrounded by great opportunities - there are three mountains that you can climb within 10km of the city proper, and there are no less than 3 game reserves within an hour's drive. These game preserves are off the main tourist track so when we went to visit Majete Wildlife Reserve we had the park to ourselves - we saw one other car for the 6 hours that we were there. Combine the ease of access with the low entrance fee ($20 including gas to and from the park) and it's a perfect place to escape from Blantyre. I didn't expect much from the park - it looked fairly small on the map, but as soon as we drove in my mistake became apparent. The entrance to the park is next to Kapuchiri Falls, which stopped the famous Dr. Livingstone on his first attempt to travel up the Shire River into Malawi. On our way up from the falls we had to stop the car suddenly - 5 elephants chose that moment to cross the road and start grazing about 20 feet away from our car. Violating the first rule of animal safety, I of course got out of the car to take a few pictures (totally worth it) and through dumb luck or the elephants' friendliness I escaped unharmed (although we left the door open in case I should need to sprint back into the car and drive away).

After spotting the elephants we hit a bit of dry spell (not that I'm complaining) were we saw mostly elands, impalas, and sable until reaching the "Hippo Spot", where, true to it's name, about 10 hippos were basking in the sun and sitting in the river. We carried on from this point to a loop around the park (thick underbrush does not a good chance to spot animals make) and were surprised by a massive herd of impala (60-80 strong) leaping across the road with four zebra in pursuit. The impala can jump - their hind legs go above their head and the highest point and it looks like the twisting will either break the back or force them to to tumble down, but they always seemed to land without even breaking stride. The park was devastated by poaching in the '80s and '90s, but starting in 2006 it has been the focus of an intensive plan to repopulate the park and increase the diversity. They've successfully imported 75 elephants from Liwonde National Park, and the herd now numbers 150. There are supposedly 7 rhinos hiding in the park somewhere, but they are rarely seen. The rangers also plan to introduce lions to the park in 2012, which will be a shock to the complacent population of grazers (I hope all the elands and zebras remember how to run...) but should also bring more visitors to the park.

The World Cup starts in South Africa this weekend, and excitement is building, especially here in Africa. As if that weren't enough, qualifications are in progress for the African Nations Championship and soccer fever is in full swing here. This fever is somewhat infectious, so when Angola played Malawi over the weekend here in Blantyre we jumped at the chance to get tickets and see the game. Seating was sold by three levels: open seating (no overhead protection from the sun and the rain), covered seating (you get to sit in the shade), and "VIP" seating (you also sit in the shade, but I think you are closer to the field). The weather was nice, so we decided on open seating (the fact that we are cheap may also have influenced this decision).

The stadium itself is a rather precarious concrete structure which looks as if collapse is a real possibility, but it's a very nice venue to watch a game - the open seating means that you can sit as close to the centerline as you dare (the rowdier locals, many of whom consume prodigious amounts of ethanol before entering the stadium, tend to prefer these seats as well) and the seats are close enough to the field where even the nosebleeds can get a good sense of the game. Getting into the stadium is an experience in itself, and the vendors who set up shop outside sell everything from coke to candy to small roasted birds on a stick (if you're feeling adventurous you can buy roasted mice with the fur intact). We arrived a bit later than planned and sat close to one of the goal lines, but our seats were right next to the stairs leading up the bleachers. This placement led to us "befriending" many of the aforementioned locals, who were shocked to see an azungu (friendlyish word for whitey) in the stands (not all too surprising, given that we one of 15, and 8 of them chose the more expensive seats).

The game itself was interesting - Angola's players seemed to suffer from a spate of sudden injuries during Malawi's drives for the goal, although thankfully these injuries resolved themselves rapidly after play had stopped and they had been taken to the sideline. The first half saw the most excitement when Angola scored 2 goals within 5 minutes, and Malawi couldn't catch up in the second half. Although Malawi lost, where else can you watch two national teams play each other for less than $2.00?

Working at a research institute is not always the most thrilling of pursuits (most of my internship involves staring at computers and working with databases) and it's always nice to escape the office for a while. In Michigan there aren't too many hilly places to go (the worst thing about the Midwest) so I was glad to find mountains all around Blantyre when I arrived in Malawi. Three mountains - Ndirande, Michiru, and Sochi - make a rough triangle around the city, and each one is self-contained nature preserve. Mt. Michiru was our first target, for no other reason than it was the closest and had a mountain to climb (the hint that leopards still lived in the park didn't hurt either). With our goal in mind, we sent off to Mt. Michiru over a less-than-perfectly-maintained road (yay for 4WD!), dodging monkeys and baboons along the way (I may have exaggerated slightly). We went up later on Saturday than planned, and by the time we got there the temperature was a bit high to attempt to climb to the top and decided to take a shorter trail that led over some hyena caves (we didn't see them, but if you stand right on top of one you can smell them - they smelled like wet dog). Other than this non-encounter with hyenas, monkeys were the most exciting wildlife on the hike (our guide was incredulous that we did not have monkeys in the US - in his words "No monkeys? Not even in National Parks!?!").

We returned to Mt. Michiru on Sunday and made it to the top this time - unfortunately, the weather was not cooperating and all we could see was the middle of the cloud bank that covered the summit (the picture shows how wonderful the visibility was). Although the mountain was only about 5,000 feet high, Malawi has not yet adopted the switchback - so the trails often go straight up the mountain. The benefit to this approach is that the trails are much shorter, but the downside is that people who are not-so-in-shape (like myself) have a more difficult time of it. Sadly we didn't have any encounters with Large African Mammals, but a group after us was running up the mountain away from a large viper. Since the mountain is easy to get to and has some pretty quick hikes that get you out of the city and into the field I'm sure that I'll be heading back fairly often during my stay.

After nearly 40 hours of continuous travel through three countries, including 3 flights, 2 (long) layovers, and a volcano scare, I've finally made it to Blantyre, Malawi, where I'll be working on my summer internship. Jet-lagged and confused, I landed in Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi, where I met a staff member from the Malaria Alert Center who happened to be in Lilongwe for sample collection and drove me down to Blantyre.

The road from Lilongwe to Blantyre was technically a highway, but not what you or I think of as a highway. Highways in Malawi are used by everyone - pedestrians and bicyclists often outnumbered the cars, and as it got darker I began to realize why traffic accidents are a leading cause in sub-Saharan Africa (hint: horns are not always effective at getting a cyclist or pedestrian to scoot over quickly). Most stalls, selling everything from fruit to cell phones to birds on a stick (fun fact: you can buy 5 roasted birds for 100 Kwacha, less than a dollar) set up right along the roadside - there are no real exits or even places to pull over safely off the road.  The scenery was amazing. What struck me first is how different everything is - the crows here have a whit torso, but otherwise look like the crows at home and the trees look different, although I can't quite put my finger on why that is. The daily life in Malawi is, obviously, very much not like that in America, and it's easiest to see in how young the population is (most people look to be younger than 25) and by how much work the children have to do. I saw at least 20 kids under the age of 8 herding goats and cattle on the side of the road - one 6-year old was able to herd 20 cattle with just a stick and lots of running. So after the trip, I'm finally settled in to the guesthouse in Blantyre and ready to start my summer internship - I can't wait.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed