Mt. Michiru is a good-sized mountain, and since it makes for a nice outing on the weekends, we decided to climb it again this Sunday (this time the top wasn't covered in a fog bank, but we still didn't make it up early enough to avoid the dust and haze, so it looks like we'll have to return at some point). The only problem with this hike is the trails, which go straight up the hill. When the sun is shining, this approach is not so much fun (I'm not sure I'll ever adjust to the fact that it can be over 90 degrees in the winter here), so when we made it back down we were in need of some sustenance.

Fortunately, the drive from Mt. Michiru to the guesthouse passes through a market area, so we stopped off to pick up some food. Bananas, tomatoes, potatoes, and chickens (alive and dead, but in neither case plucked) were the most common items on offer, and since it is the sugarcane harvest season we also passed a few buckets of freshly harvested cane. Being the adventurous sort, we decided to stop and pick up some bananas and two sticks of cane - all for less than $0.70. Both were delicious and made for a great snack after coming down the mountain, although eating the sugarcane was much more labor-intensive than I had expected - first you have to strip the bark (using a knife is smart but the Malawians use their teeth), and then you can get to the fibers which are soaked with the sugary water. Still, totally worth the $0.15 per stick.

Working at a research institute is not always the most thrilling of pursuits (most of my internship involves staring at computers and working with databases) and it's always nice to escape the office for a while. In Michigan there aren't too many hilly places to go (the worst thing about the Midwest) so I was glad to find mountains all around Blantyre when I arrived in Malawi. Three mountains - Ndirande, Michiru, and Sochi - make a rough triangle around the city, and each one is self-contained nature preserve. Mt. Michiru was our first target, for no other reason than it was the closest and had a mountain to climb (the hint that leopards still lived in the park didn't hurt either). With our goal in mind, we sent off to Mt. Michiru over a less-than-perfectly-maintained road (yay for 4WD!), dodging monkeys and baboons along the way (I may have exaggerated slightly). We went up later on Saturday than planned, and by the time we got there the temperature was a bit high to attempt to climb to the top and decided to take a shorter trail that led over some hyena caves (we didn't see them, but if you stand right on top of one you can smell them - they smelled like wet dog). Other than this non-encounter with hyenas, monkeys were the most exciting wildlife on the hike (our guide was incredulous that we did not have monkeys in the US - in his words "No monkeys? Not even in National Parks!?!").

We returned to Mt. Michiru on Sunday and made it to the top this time - unfortunately, the weather was not cooperating and all we could see was the middle of the cloud bank that covered the summit (the picture shows how wonderful the visibility was). Although the mountain was only about 5,000 feet high, Malawi has not yet adopted the switchback - so the trails often go straight up the mountain. The benefit to this approach is that the trails are much shorter, but the downside is that people who are not-so-in-shape (like myself) have a more difficult time of it. Sadly we didn't have any encounters with Large African Mammals, but a group after us was running up the mountain away from a large viper. Since the mountain is easy to get to and has some pretty quick hikes that get you out of the city and into the field I'm sure that I'll be heading back fairly often during my stay.

After nearly 40 hours of continuous travel through three countries, including 3 flights, 2 (long) layovers, and a volcano scare, I've finally made it to Blantyre, Malawi, where I'll be working on my summer internship. Jet-lagged and confused, I landed in Lilongwe, the capital of Malawi, where I met a staff member from the Malaria Alert Center who happened to be in Lilongwe for sample collection and drove me down to Blantyre.

The road from Lilongwe to Blantyre was technically a highway, but not what you or I think of as a highway. Highways in Malawi are used by everyone - pedestrians and bicyclists often outnumbered the cars, and as it got darker I began to realize why traffic accidents are a leading cause in sub-Saharan Africa (hint: horns are not always effective at getting a cyclist or pedestrian to scoot over quickly). Most stalls, selling everything from fruit to cell phones to birds on a stick (fun fact: you can buy 5 roasted birds for 100 Kwacha, less than a dollar) set up right along the roadside - there are no real exits or even places to pull over safely off the road.  The scenery was amazing. What struck me first is how different everything is - the crows here have a whit torso, but otherwise look like the crows at home and the trees look different, although I can't quite put my finger on why that is. The daily life in Malawi is, obviously, very much not like that in America, and it's easiest to see in how young the population is (most people look to be younger than 25) and by how much work the children have to do. I saw at least 20 kids under the age of 8 herding goats and cattle on the side of the road - one 6-year old was able to herd 20 cattle with just a stick and lots of running. So after the trip, I'm finally settled in to the guesthouse in Blantyre and ready to start my summer internship - I can't wait.

It's hard to believe that I'm halfway done with my MPH - the first year went by too quickly, and the end of the year stress (finals, final projects, etc.) helped it to fly by even more quickly. After finals ended, I noticed something strange - the snow was gone and the weather was gorgeous (lows in the 50's, highs in the mid-70's... while winter is brutal it is hard to dislike MI in the spring). Given the nice new weather, I decided to explore MI a bit with another epidemiology student, and we found two nice hikes that were good escapes from Ann Arbor.

One thing that I miss in MI are the hills - I could see mountains from my undergrad and hometown, and when I worked in Germany I was in one of the hillier regions, so MI is oddly flat to me. Since I was used to this terrain, I just assumed that hiking = walking around in hills and mountains, and that hiking around a flat plain wouldn't be all that much fun. Needless to say, I was wrong. We found a bog near Kalamazoo (yes, that's a real place name) and decided that it would make for an interesting adventure, seeing as how I'd never seen a bog before. It was a nice change from the hills and mountain streams that I was used to - all of the plants were different, there were more birds, and there were a few snakes and frogs to keep things interesting.  However, the trail was probably the most fun part of the hike. It went right over the bog (I'm not sure how they did it, the plastic boards didn't seem to be anchored to the ground but they were very stable) and if you moved too quickly you could get a bit wet. We didn't expect that the trail would fight back, so the first few steps were a bit wetter than we had anticipated, but after getting adjusting for the surprising squirts it was a nice way to cool off and it always made for a nice surprise. On the way back from Bishop's Bog, we stopped at Bell's Brewery, which has some of Michigan's best local beer and should be a required stop if you find yourself in the area.

I'll be heading off to Malawi for my summer internship soon (more on that later), but when I get back to MI I'm looking forward to exploring more of what the state has to offer - especially since I'll only have one more year to take advantage of it.

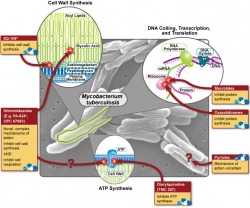

The Office of Public Health Practice hosted their annual symposium on Wednesday, and the theme was "Can the World be TB Free"? I only had a chance to attend one of the talks (by Dr. Joseph McCormick), which dealt with the rising problem of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis ( MDR-TB) and how our treatment strategies of TB may have helped this new disease to emerge. In what is sadly a familiar story for many bacterial diseases, the discovery of streptomycin (the first antibiotic that was effective against TB) was hailed as the first step in the elimination of the disease, but as time as passed the drug has become less and less effective, forcing us to search for new treatments. In the wake of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, TB has exploded and the growing problem of antibiotic resistance makes treating these people very difficult. So why does drug resistance happen, and how is it our fault? There are about 10 million (or 10^7 if you're feeling scientific) individual tuberculosis bacteria living in each cavity. About one bacteria out of every 10-100 million will randomly develop a mutation that confers resistance to any one of the two major first line drugs, rifampin and isonazid. These mutations are quite rare, but given that bacteria are nothing if not effective reproducers, it is safe to assume that approximately one bacterium per cavity is resistant to rifampin, and that another is resistant to isonazid. This situation may not sound all that bad, but consider what would happen if the patient were to be treated with rifampin alone - every single bacterium would die except for the one that had developed resistance. This bacterium is now presented with perfect growth conditions - no competition and lots of food - so it begins to multiply, and after a few days have passed, 10 million bacteria live in the cavity again - but this time all of them are resistant to rifampin. Given the large number of bacteria involved, it's now reasonable to expect that one of these resistant bacteria will then develop a resistance to isonazid, and following another single-drug treatment cycle, MDR-TB is born.

While browsing the interweb, I came across this video by Hans Rosling - probably the most amusing statistician alive today (and no, that's not an oxymoron).

Dr. Rosling teaches International Health at the Karolinksa Institutet (like Harvard, but in Sweden), and is also the Director of the Gapminder Foundation. Gapminder has some more amusing videos on their site and they take health issues, like HIV/AIDS, and present them in an entirely new context. What I especially like about the site is that they recognize that the issues are complex and that simple solutions probably don't exist (you can see this at the end of the above video when he says that he supports the media coverage, but warns us not to read into it too much).

After a few days of lounging on the beach and reading, we decided to explore the island of Maui in a bit more depth (lounging around is nice and all, but I tend to get a bit stir crazy after a few days). I hadn't gotten the chance to go diving in over a year (it seems like a lifetime ago when I was in the water at least twice a day on the weekends) so when I had the opportunity I jumped at the chance. The site of my first dive after the hiatus could not have been better - a shallow reef inside the remains of a volcanic crater. While it was nice to be underwater again (I was surprised at how quickly my buoyancy control came back to me), the clear highlight of the dive was listening to the humpback whales underwater. The crater is shaped like a half-moon, and the hard rock walls amplify and reflect all the sound that comes into it, making it one of the best underwater spots to hear whales singing. And it wasn't just underwater that we found whales - they are everywhere around Maui this time of year, and we saw close to a dozen on the boat ride between the harbor and the dive site. Sadly, none of them breached, but you can't have everything...

The day after the dive trip (which turned out to be more chaotic than I'd have liked - my dive computer flooded and I almost left my camera on the dive boat...), we found ourselves with access to a rental car, thanks to the arrival of my friend's sister. The weather was not outstanding as we drove around the island (in case the giant crashing seas in what is supposed to be a tropical paradise didn't give that away), but we made the best of it and trekked to blowholes, swimming holes, and the best banana bread stand in the world. Getting to the banana bread stand was the hardest part - although we had to climb over lava rocks to get to the swimming holes, getting to the banana bread stand required a fairly long drive up one-lane cliffside road, with a good amount of traffic moving in both directions. The village that the banana bread was in was worlds apart from the resort complexes that most people think of when they imagine Hawaii - it was a very rural and economically depressed area, and it didn't look like many visitors made it to that part of the island.

Sadly, there was one major disappointment of the trip. We woke up at 3AM to go watch the sunrise over a volcanic crater, but the weather conspired against us - after two hours of standing in a cloud/fog bank/something cold and very damp, all that happened when the sun rose was that the cloud turned from black to a lighter shade of dark gray. Inspiring it was not, but now I have a reason to go back. Following the mountain adventure, we headed down to Pa'ia to sit on the beach for one last time, and then it was off to the airport to fly home to Michigan. When I made it back, there was still snow on the ground (which has thankfully since melted).

For more pictures, you can check out the gallery here.

So what exactly is public health? If you've ever wondered about this question, you're not alone - the Association of Schools of Public Health realized about a year ago that most people don't really have any idea what public health professionals do, so they made this handy website and the video below. ( Link to the video in its original context.) One of the coolest parts of this campaign: you can get the stickers for free! I like the idea of the ASPH's campaign and think it's great that the video shows a lot of public health's "hidden" aspects, but I wish that the video would show some of the dramatic effects that public health has had on society. While public health is a very broad field, it doesn't include everything (although it's a fun game to try to find some connection to public health in everyday objects - think "Six Degrees of Separation" for public health dorks). The best example is smoking - once it became clear that tobacco smoking was a major health hazard (from epidemiologic research), programs to help people quit started (thanks to Health Behavior and Health Education), and eventually policy changes were made (courtesy of Health Management and Policy) so that smoking is now banned in public places in most states (MI recently passed such a law). Other examples of changes made by public health professionals are as basic as the regulation of drinking water and ensuring that our food supplies, especially meat, remain disease-free. Going back to infectious diseases, the national vaccination program has eliminated almost all of what were formally the "childhood diseases" - no-one born in my generation has had to experience widespread polio, measles, or whooping cough outbreaks. (A list of the 10 greatest public health achievements is found here). So as a tool for raising awareness, the video is great, but I hope that it encourages people to look deeper into public health. There really is something for everyone in this field, from microbiology nerds (like me) to policy wonks (how else would we get public health laws passed?).

Last Friday, I left 1 1/2 feet of snow on the ground in Ann Arbor and headed to Maui for spring break (it's a rough, rough, life). It was a transition in more ways than one - I was not even close to ready for the 60 degree temperature increase or the fact that I suddenly found myself with the free time to sit down and read a book (4 down so far). The week started off with a somewhat overhyped tsunami warning (all that happened was that we were confined to our hotel for a few hours), but even tsunami warnings are enjoyable in the Aloha state - from the balcony we could see humpback whales breaching in the distance. The scenery is also a nice change from Hawaii - rainforest-covered mountains are a far cry from the flat and snowy midwest.

But after a week of lounging, scuba diving, and accidental whale-watching ( humpbacks seem to pop up everywhere here) I'm excited to get back to work. Epidemiology seems to have worked its way into my head and I keep finding odd connections and epidemiologic puzzles, even while on vacation. The best example of this comes from sea turtles, of all places. While snorkeling, we saw a sea turtle that had 5-6 baseball sized tumors on it's neck, flippers, and tail. Curious as to what caused the tumors, I've been asking around but it appears that everyone is stumped (even scuba instructors, normally a source of good info - or at least willing to make something up as long as it's interesting - also didn't have a clue). Like any good scientist, my first thought was to turn to google. After a few minutes of intense digging (it is still vacation, after all) I found this site. From a modest beginning with only a few sightings reported in the 1960's, it is now believed that the disease afflicts more than 60% of Hawaii's green turtles and is sadly often fatal. Although the cause remains unknown, one theory is that the disease is caused by a virus and that it will soon reach epidemic proportions in other sea turtle populations. Now if only I could convince UM SPH to let me study that outbreak...

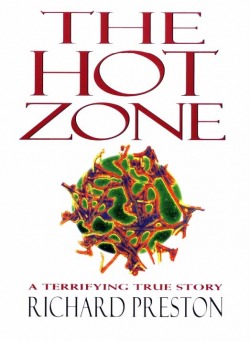

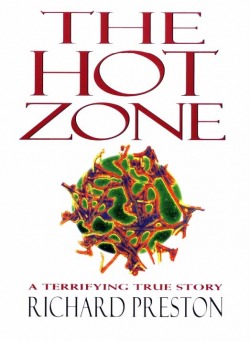

I have a confession: for a long time, I was pretty unclear on what public health, much less epidemiology, actually was. Given the state of public health in the media (you only hear about it when something goes horribly wrong...), it's not all that surprising. However, we have public health to thank for many of the things that we currently take for granted - like the idea that smoking is dangerous and the elimination of many once-dreaded childhood diseases like measles and polio. My interest in the field of public health in general, and epidemiology in particular, began when I read Richard Preston's The Hot Zone and I continued to be inspired by popular accounts of how epidemiology interacts with modern life in very hidden ways.  If you think that you might have even a passing interest in public health, I encourage you to check out the two books above. They each highlight why epidemiology is such a fascinating field, but they approach it from two different directions. My favorite of the two is The Hot Zone, which follows the US Army's attempt to contain an Ebolavirus outbreak (yes, that Ebola) in Reston, VA (yes, the one next to Washington D.C.). The book has some fairly surreal scenes - like an army clean-up unit staring at a busy playground while the suit up to enter an infected monkey house in secrecy - and it may or may not have contributed to a slightly romanticized view of what epidemiologists actually do (sadly, so far we've not been mobilized to contain any outbreaks and I've not had to run tests on infected monkeys). But the book does highlight the extraordinary level of surveillance that our public health officials must maintain and the variety of situations that they need to be prepared to handle.

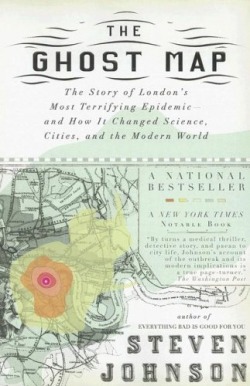

Stephen Johnson's The Ghost Map takes a different approach to public health - how it can be used to clean up after a disaster. In the mid-19th Century, people began flocking from the countryside to the city, creating the lifestyle that most of us now take for granted. The population of most major urban centers exploded, and to borrow a phrase from Johnson, London was "... a Victorian city with an Elizabethan infrastructure." The recent conquest of India brought a different kind of immigrant to England's capital - Vibrio cholerae, a nasty bacterial species that causes cholera, which produced extremely severe diarrhea. From 1853-54, a cholera outbreak killed 10,000 people in London, and The Ghost Map tracks how the cause of this disease was discovered and how the later public health improvements helped create what we think of as modern urban infrastructure.

Both books are great reads, especially if you think you might be interested in this thing called "public health" - and yet they only scratch the surface of one aspect of one part of one discipline of the whole. There's lots more good books out there - The Coming Plague comes to mind, and I'm sure that some of you may have suggestions of your own.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed